FARO.com

FARO is the leading brand in 3D measurement technology used in factory work, public safety and now forensic anthropology. The FARO® Forensic ScanArm solution was designed specifically for criminal investigations.

When used with 3D Systems Geomagic® software, the ScanArm allows scientists a noncontact way to scan items of forensic interest in high resolution. It is armed with blue laser technology, which boasts noise-free scanning in high detail at high speeds.

According to the website, it is easily portable. So, it isn’t just some piece of expensive sitting equipment. Theoretically, you could get the scan done before you even take the remains or whatever items to the laboratory.

Despite those claims, it might not be the ideal field equipment the company hoped it would be:

@sianysmith @amdenardo I wouldn’t say that it’s very portable-it takes several people to lift the cases as the scanner+stand are so heavy!

— Tom O’Mahoney (@bones2bytes) August 29, 2016

However, this doesn’t take away from all the good things about the equipment.

The interface is designed so that people without 3D imaging experience should be able to navigate it. With 3D imaging being a newer discipline and with its rapid technological advancement, this is important. One day, scientists will probably be able to use 3D scanning devices as easily as they can use a laptop. For now, the transition is still underway, and easy-to-use interfaces will be very helpful for both the people making the scans and the ones making the scanners.

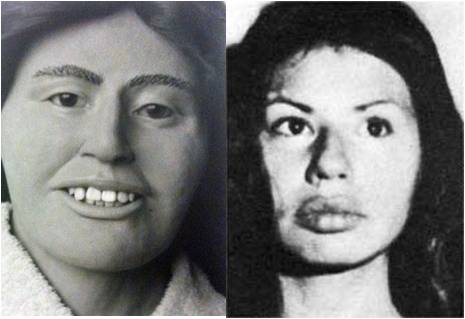

We talked about 3D copies of skulls for facial recognition in another post. The ScanArm bears the same significance as it means to enable scientists to make these copies with the newest technology and be able to work with sturdy evidence. That is, to make identifications without damaging fragile human remains or other evidence.

“By listening to our rapidly growing base of Public Safety – Forensics customers, we have learned that thoroughly measuring and analyzing forensic evidence is of paramount importance. Our non-contact measurement tools allow forensic labs to meet this requirement while minimizing the risk of damaging the evidence. It is now possible to produce accurate and permanent 3D digital documentation of evidence from which measurements can be taken and analysis can be performed days or even decades later…” –Joe Arezone, Chief Commercial Officer of FARO

The key here is “noncontact.” According to this statement, it is no longer necessary to handle the remains or risk damaging them. Further, there are no sprays necessary for the laser to scan, so there is no apparent risk for contamination.

The ScanArm isn’t only to aid forensic anthropologists, however. It is designed for crime labs to create a digital archive of evidence to store for years to come as well as to use in court presentations. Medical examiners can use the ScanArm to digitally collect traumatic injuries quickly.

FARO.com

Another key is the speed with which these operations can be handled. Officials desire forensic investigations to be handled with care, but mostly with speed. And it is even worse when forensic anthropology and archaeology is a component of the investigation. It is hard work. If the ScanArm hopes to be successful, it will need to do the work accurately without taking away time from an already quickly ticking clock.

I can’t wait to see how else scientists will think to use the ScanArm and if it will live up to the high claims made by FARO.

Click here to learn more about the ScanArm and to schedule a personalized web demonstration.

FARO.com