Last week, we heard about the set of mystery remains that were found in a field in Texas in March. I had a chance to catch up with officials on the case to talk about how a real investigation is conducted and clarify some inconsistent news reports about the case.

“Please understand why law enforcement is sometimes reluctant to work with the media,” McBride said. “The frustrating part of using the media is that sometimes they don’t report what we give them accurately. In any (media) report, there is usually something that is inaccurate, lost in translation or just sounds better to the reporter, but has lost context because it was changed. I know it’s not done with malicious intent, but this is the result.”

KSAT Antonio reported a range of heights for the individual and The Seguin Gazette reported an exact height of 5’2”. Those sources also had inconsistent information about the amount of time the individual has been in the field, which is less than two years and more than one month. These inconsistencies were mostly due to the change of information as it became available.

Investigator Sgt. Zachary McBride of the Guadalupe County Sheriff’s Department confirmed that the woman’s height is estimated to be between 5’0” and 5’6”, while the preliminary report’s minimum height was 4’11”. Five-foot-two inches is the middle data point for the height range.

Before the height was ever determined, however, a lot went into the location of the skeleton.

“While the majority of the bones were spread over the field due to plowing activity, the skull was found mostly intact with only the left part of the maxilla missing,” McBride said. “This was recovered a week later and fit perfectly into the missing part of the skull.”

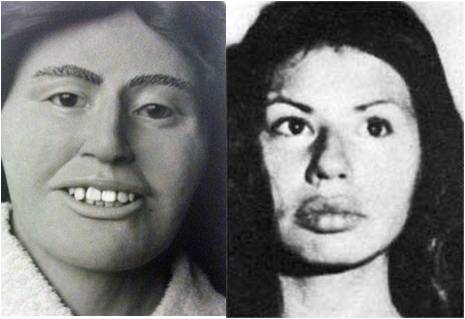

The department, through the Texas Rangers, will use a 3-D printed copy of the skull in order to reconstruct the face of this unidentified female. An artist from the Department of Public Safety will undertake the task of reconstructing the face.

In addition to the identification of the remains, the department is tasked with compiling evidence and admissible witness and suspect statements.

“We have recovered all the evidence we can locate,” McBride said. “There are no known witnesses (the neighboring areas have been canvassed) and of course no known suspect. The investigation can really only begin once we know our victim’s identity and use a time line from when she was last seen to build the investigation from that point.”

A decomposing body at the Texas State body farm.

Dr. Daniel Wescott

Original Source

Sgt. McBride is working with Dr. Daniel Wescott at the Forensic Anthropology Center at Texas State University.

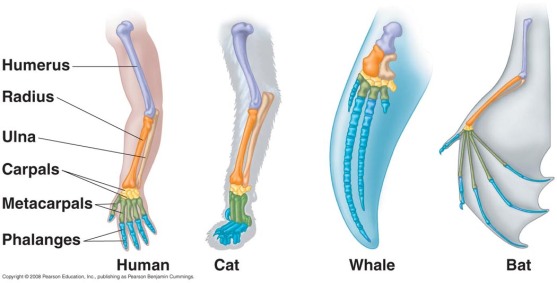

Dr. Wescott and the other investigators had to search for and map evidence, transport the remains to the laboratory and do a full work-up. This means they conducted a biological profile (sex, ancestry, age, etc.), documented dentition and examined the bones for trauma and taphonomic damage, which includes preservation and signs animal scavenging. This information was entered into the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, or NamUs database. Lastly, DNA samples were sent to be analyzed in hopes of getting a match.

The role of the forensic scientist isn’t complete at this point.

“We also will aid law enforcement in the exclusion of individuals or the positive identification of the person,” Wescott said.

When asked about the possibility the remains belonged to an undocumented individual, whether there was clothing or other effects found in the field, and what the cause of death was, officials refrained from answering – and for good reason.

“The answer to those questions are controlled information that we would use to test the truthfulness of a witness or suspect if we ever interview them,” McBride said. “I have experienced cases where witnesses will intentionally lie or just misremember details. I have had suspects give ‘false confessions,’ for whatever reason. If the witness or suspect is able to correctly answer these questions you are asking without the answer being in the public domain, it lends credibility to their statement.”

For this reason, there is information for cases like these that is limited to the investigators and involved parties. Some leads were ruled out using dental records against local missing persons. This ongoing investigation will continue to pursue local missing persons.

“In the end, it will be DNA and/or dental records that identify our victim,” McBride said.

It takes time to change beliefs that have been so ingrained over time. It seems

It takes time to change beliefs that have been so ingrained over time. It seems